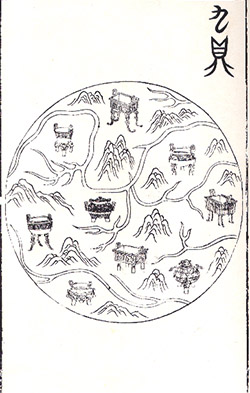

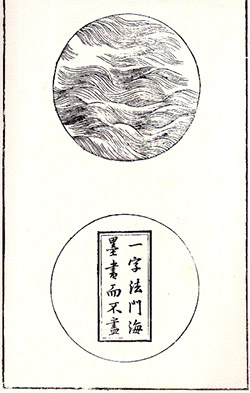

| Like plastic in our time, ink is a material 'without grain,' a pure substance that can be precisely cast into shaped inkcakes. This allows ink to serve as a medium for complex expression on an intimate scale. A further poetics occurs in use: slowly, methodically, an inkcake is ground in a puddle of water to become ink. An elegant sacrifice, this progressive dissolution of consummate craft suggests a metaphor that would resonate in creative life – of effort and skill returned to origins, of transformation of substance. And this in common stationary! The Ming period (1368-1644) saw a substantial production of inkcakes as collectibles. Large, palm-size inkcakes were made by workshops with national distribution networks. Mixing Taoist, Buddhist and natural images with literary inscriptions, the inkcakes of this time were luxuriously offered to buyers through large format woodblock printed catalogues. In these four examples from the 方氏墨譜 catalogue, one finds diagrams of sacred landscapes, meditative water (showing front and back of the inkcake), archaic 'bird and serpent' calligraphy (with the text transcribed in a contemporary font for the reader), and traditional Taoist talismans (again, front and back). | |

|

|