Feature Contents

Some random notes for my daughters - on enjoying paintings | back to feature home |

|  |

The images you have here are a printed copy of the most recent remounting. To remount paintings is a difficult procedure as it involves stripping the thin painted papers from the thicker pages to which they are glued, like taking skin away from muscle. Despite the professionalism of generations of mounters, this is surgery, with all the risks of trauma and damage beyond repair. It involves not only peeling back the paper of the painting, but removing mildew and stains with pure water, liquid cleaners or crude scraping.

You should visit a mounter's workshop sometime. My impression is that little about the work has changed for several centuries. The glues are still made of old animals and fresh vegetables, though perhaps modern mounters worry less about aging the glue now. A visitor to the backroom where the work really takes place sees the task much as it has always been. In the middle of the room sits a huge smooth table (such tables were once thickly lacquered) with drawers that hold some very sharp knives, spatulas, thick brushes and containers of liquids. Cabinets on one side contain more tools, glues and rolls of paper or silk for the backings and the decorative front mountings. The walls of the room are essential to the work and at any moment they are likely to be covered with paintings that seem to be glued to the wall itself. This is what will happen to those that one brings, as the arrangement for drying the mounting glue consists in fixing the edges of the backing paper to the flat wall. The painting and its mounting will dry without warping, and will be crisp and flat when taken down. Besides the work currently on the wall, the walls are covered with the detritus of many years of glue and paper.

In addition to fixing the paintings onto a new backing, the mounter may attend to those portions of the painting that have been consumed, filling the gaps with new touches of ink and colour. Is it any surprise that the great mounters may also have been the great forgers, and were sometimes accused of duping their clients with reproductions returned in place of the originals entrusted?

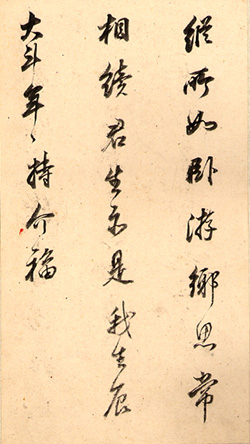

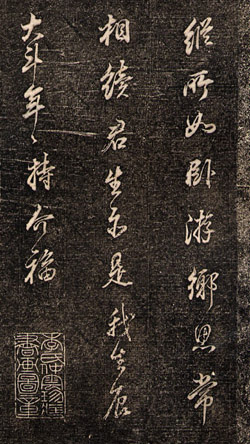

But remounting is only the responsibility that comes of preventing outright loss. More fascinating is the subtle renewal of arrangement and presentation. The unimaginative owner will be content to add his own writing onto a page pasted at the end and perhaps to add a few seals here and there as a souvenir of his passing. Or he might press some talented friend into writing a frontispiece in a good hand. More delicate is to re-arrange the pages and to renew the mounting and binding in a manner that enriches. For instance, one might add decorative pages back and front, commission a cover in burl wood, or simply have the title written well and pasted on the outside. Or, as with an album of calligraphy that I once examined, one might have the whole work engraved on stone. The rubbings made from the stones are like a photographic negative, the characters now appearing in white on black as a consequence of the incised carving. A set of rubbings was then added to the album, following the original calligraphy as its double and its echo. The only difference in the engraved version being a refinement discovered only by close inspection: a new seal of the collector that does not appear on the original.

You should visit a mounter's workshop sometime. My impression is that little about the work has changed for several centuries. The glues are still made of old animals and fresh vegetables, though perhaps modern mounters worry less about aging the glue now. A visitor to the backroom where the work really takes place sees the task much as it has always been. In the middle of the room sits a huge smooth table (such tables were once thickly lacquered) with drawers that hold some very sharp knives, spatulas, thick brushes and containers of liquids. Cabinets on one side contain more tools, glues and rolls of paper or silk for the backings and the decorative front mountings. The walls of the room are essential to the work and at any moment they are likely to be covered with paintings that seem to be glued to the wall itself. This is what will happen to those that one brings, as the arrangement for drying the mounting glue consists in fixing the edges of the backing paper to the flat wall. The painting and its mounting will dry without warping, and will be crisp and flat when taken down. Besides the work currently on the wall, the walls are covered with the detritus of many years of glue and paper.

In addition to fixing the paintings onto a new backing, the mounter may attend to those portions of the painting that have been consumed, filling the gaps with new touches of ink and colour. Is it any surprise that the great mounters may also have been the great forgers, and were sometimes accused of duping their clients with reproductions returned in place of the originals entrusted?

But remounting is only the responsibility that comes of preventing outright loss. More fascinating is the subtle renewal of arrangement and presentation. The unimaginative owner will be content to add his own writing onto a page pasted at the end and perhaps to add a few seals here and there as a souvenir of his passing. Or he might press some talented friend into writing a frontispiece in a good hand. More delicate is to re-arrange the pages and to renew the mounting and binding in a manner that enriches. For instance, one might add decorative pages back and front, commission a cover in burl wood, or simply have the title written well and pasted on the outside. Or, as with an album of calligraphy that I once examined, one might have the whole work engraved on stone. The rubbings made from the stones are like a photographic negative, the characters now appearing in white on black as a consequence of the incised carving. A set of rubbings was then added to the album, following the original calligraphy as its double and its echo. The only difference in the engraved version being a refinement discovered only by close inspection: a new seal of the collector that does not appear on the original.