Private and institutional collecting

Private collecting – visions and circumstances

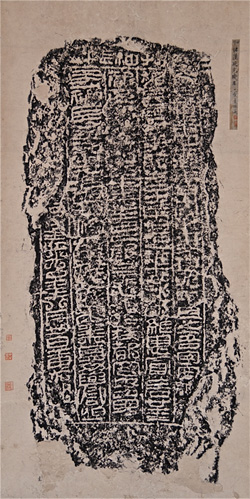

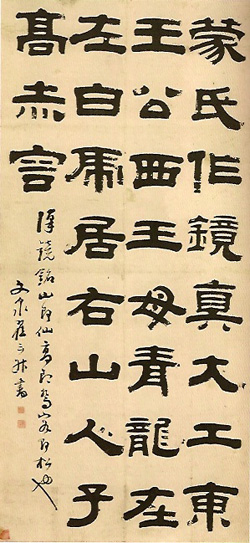

Every time creates its own view of the past, with, for instance, relative preferences for one set of painters or individual paintings over others. Often this relates to contemporary social issues and formal currents in art. Among Chinese scholars and collectors of the mid and late Qing, the attention given to studies of early history and philology resulted in the collection of inscriptions from bronzes and ink rubbings of early stele. The revival of interest in ancient seal-form as a style of calligraphy arose in tandem with this. Often contemporary religious or philosophical tendencies inform preferences. Elaborate Buddhist rites and piety have repeatedly led to the collection and production of descriptive, detailed and ritualistic art. Often esoteric, this has included paintings of arhats, sutra calligraphy, and ceremonial objects. While, contrastingly, attention to Taoism and Chan (or Zen 禪) Buddhism has aligned with a preference for more restrained and suggestive forms. The collecting of Chinese art outside of China has similarly been influenced by local history and interests. For instance, Japanese collectors at various moments have preferred particular Chinese styles, such as the Chan Buddhist paintings that entered Japanese temples with returning disciples in the Song (960-1279) (and which have hardly survived in China), or styles of Ming calligraphy that struck a cord with Japan’s own calligraphic manner. Now, with the repatriation of materials from Japanese collections into the Chinese auction market, the shape of Japanese taste is often strongly evident in recurrent compositions and brush techniques (as well as in particular Japanese taste for mounting scrolls and albums). In the early twentieth century, as Chinese art became known in Europe and America, the representational art of the Song (960-1279) appealed to collectors steeped in the idyllic of late Impressionism – and many of the pieces they collected came to be seen as ‘typical’ of Chinese painting by subsequent generations. By contrast, early statuary was collected in tandem with an interest in global primitive art (and contemporary abstraction), and calligraphic arts were championed in America when Abstract Expressionism was at its apogee. Japanese and Euro-American reception has varied in one important dimension. Japanese traditionally appreciated Chinese art as a canon to aspire to, a wellspring of their own culture. By contrast, Europeans and Americans have valued Chinese art as one among several Others that serves as a foil to the ‘mainstream’ or ‘reference’ of their own art. |  Ink rubbing of Han stele (206 BCE–220 CE) 19th century rubbing Hanging scroll Private collection |  ZHAI Yunsheng 翟雲升 (1776-1860) Calligraphy in seal script Hanging scroll, ink on paper 158 x 73cm Private collection |